Among other attractions at Canyon de Chelly the major ones are the magnificent scenery and the Anasazi or Pueblo ruins.

The rim of the canyon is at an elevation of from 5700 feet up to about 7300 feet and ranges in depth from just a couple hundred feet to just over 1000 feet. The National Park is actually several canyons carved by several streams coming together just east of Chinle. The major canyons are Canyon Del Muerto to the north and Canyon De Chelly to the south. Most of what you see as the walls of the canyons is what's called de Chelly Sandstone, deposited some 250 Million Years Ago (MYA) - this layer is a light red rock formed from desert sand dunes. In many places where erosion has exposed it, you can see the "grain" and shape of the sand dunes. Over that is a thinner layer of what's called Shinarump Conglomerate, deposited only 200 MYA - this grayish-brown caprock was deposited by stream action.

This map will give you a good idea of the layout. The map is about 13-14 miles on each side.

I am staying at the Cottonwood Campground next to the Visitor Center.

Here's

the view from the Ledge Ruins overlook. These are the real colors!! The

trees on the floor of the canyon turning yellow are Cottonwoods. Other major

plants are the Tamarisk and the Russian Olive. Those three were introduced

by the Park Service in the 30's in an attempt to control erosion. The floor

of the canyon looks dry. It is, sorta. You can dig anywhere on the canyon

floor and hit water within two feet - and this is the dry season. Even

though it's the dry season, there are still wet areas in the sand, and even

quicksand in places where the underground flow is brought close to the

surface by underground stone formations. In the spring, the floor of the

canyon is covered with run-off from the surrounding land. In fact, it's not

until late spring when the water starts to subside, that the Navajo can get

into the canyon to plant. From where I stand taking this picture, the canyon

wall is some 400 feet tall.

Here's

the view from the Ledge Ruins overlook. These are the real colors!! The

trees on the floor of the canyon turning yellow are Cottonwoods. Other major

plants are the Tamarisk and the Russian Olive. Those three were introduced

by the Park Service in the 30's in an attempt to control erosion. The floor

of the canyon looks dry. It is, sorta. You can dig anywhere on the canyon

floor and hit water within two feet - and this is the dry season. Even

though it's the dry season, there are still wet areas in the sand, and even

quicksand in places where the underground flow is brought close to the

surface by underground stone formations. In the spring, the floor of the

canyon is covered with run-off from the surrounding land. In fact, it's not

until late spring when the water starts to subside, that the Navajo can get

into the canyon to plant. From where I stand taking this picture, the canyon

wall is some 400 feet tall.

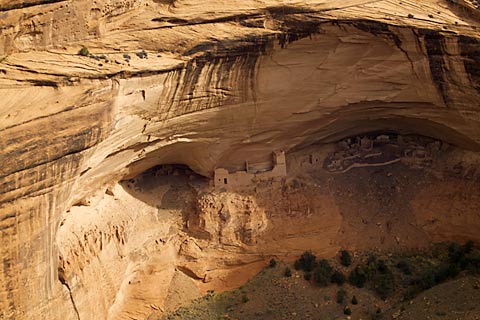

Here's a shot of the Ledge Ruins. This ruin has living and storage areas, kivas (rooms for religious ceremonies), and a two-story structure in the back of the central alcove built 900 years ago by the ancient Puebloans.

The formation of the canyons is from various forms of erosion. One, exfoliation, occurs when water seeps into cracks, freezes and exerts enough pressure so that huge slabs of the wall peel off and falls to the floor of the canyon. Most of these cities were built into an overhang created when the canyon wall "exfoliated" and created a protected alcove - as seen above.

Many of the ruins in the canyons appear to be too far off the floor of the canyon for habitation. The best guesses I heard, from both park people and from the Indians, is that when the "cities" were built, erosion was not as bad as it has been in the past couple hundred years, and the floor of the canyon was much closer to the dwellings. Each of the ruins is a city - this particular one had some 40-50 rooms and probably housed 40 or so families. Still, the city would have been off the floor of the canyon to protect it from the seasonal floods running through the canyon, and to protect it from enemies. Access would have been by ladder, footholes carved in the rock or poles imbedded in holes carved in the rock. Some of those features can still be seen in places.

Here's what's called the Mummy Cave Ruin - so called because when archeologists excavated the site, they found two mummies in one of the chambers. This is one of the largest villages in the the canyon and was occupied from the earliest times to about 1300. The tower complex on the central ledge is a later structure, built in the late 1200s. At this point, the canyon wall is about 500 feet tall with Mummy Cave ruin some 100 feet off the floor.

The dark "streaks" in the sandstone are what's called Desert Varnish - from manganese-fixing bacteria that live on the canyon wall in the moist areas where rainfall runs over the rim and through cracks. These bacteria take minerals from airborne dust and the water and digest it. This process "fixes" the manganese to the wall. That's one story. The other just involves water running over the rim and seeping through cracks in the wall leaving the manganese and other oxide deposits with no help from any bacteria. Take your pick. From the canyon floor and in the right light, some of the thicker sheets of varnish gleamed a bright metallic blue!

Here's a close-up of the alcove on the right above - just to give you an idea of the size of these cities.

Altogether, Mummy Cave had hundreds of rooms and probably housed an equal number of families.

Here's a shot of Antelope House - so named because of some antelope rock art attributed to a Navajo Artist, Dibe Yazhi, who lived here in the early 1800s. The canyon wall here is some 800 feet high. Tomorrow, we'll get a close-up look at this site.

After lunch and now on the south rim, here's Spider Rock. This formation is an 800 foot spire at the junction of Canyon de Chelly and Monument Canyon. It's named after the "Spider Woman" who, legend has it, taught the Navajo women to weave rugs and lived on top of the spire. To keep their children in line, Navajo women tell them if they don't behave, Spider Woman will come get them and take them to the top where they'll be eaten for supper.

Anthropologists figure the Navajo learned weaving from Mexican Puebloans from the south.

A sign seen at one of the overlooks. A prudent admonition because it would be easy for someone to take the fatal plunge. From the parking areas at the overlook, you may have to walk along the rim up to a quarter mile to the actual overlook. In some cases there is a paved walkway and in others there is a row of stones marking the route. At the overlook, there is typically a stone wall at the "designated" overlook to keep you from falling over. However, on either side of the wall, there is nothing. You can walk anywhere you want on the rim - which is what I've done. Most of my pictures were not taken from any "designated" overlook.

This is called the White House Ruin - so named because of the obvious white wall of one of the structures. Actually, the white wall is the inside back wall of the structure as the front wall has collapsed. The inside walls were frequently painted white to "lighten" up the interior from reflected light - just like we might do today. This photo is a cliché. It's been used in many magazines - by National Geographic and by many other outdoor magazines. Look at the Desert Varnish on the wall here!!

From here, we're about 500 feet above the ruin. This is the only place where you can enter the canyon without a guide. There is a trail from the overlook where I stand, down the side of the canyon to the floor and across the wash to the ruin - in all, about a 3 mile round-trip and 500 vertical feet of elevation change.

Since I might visit this one on the ground tomorrow, I decide not to do the hike. Also, it's late and I'd be coming back up the canyon wall in the dark. Those are as good excuses as any.

Here the erosion has revealed the

actual shape

and size of the ancient sand dunes that make up the sandstone layer of the canyons --

amazing geology!

"Travelers can't know where they are going until they understand where they've been" -- Unknown